Houston shelters, rescues are battling a stray animal crisis

On an exceedingly hot Sunday morning in a northeast Houston neighborhood, two pairs of jaded eyes appear from a hidden storm culvert.

“Babieeeeeees!” Anna Barbosa and Jane Wesson of the animal rescue group Houston K-911 shout simultaneously. “Babieeeeeeeees!”

The strays slowly move out from the culvert at the corner of Peach Street and Haywood. Both are covered in mange, and one has a swollen belly. They are starving and itchy.

The brown-colored stray is more trusting and slowly makes her way to Wesson’s beat-up SUV. The other keeps her distance.

A stray dog is seen on the corner of Peach St. and Haywood on May 15, 2022 in Houston. The bumper sticker on the car reads “ Animal abusers should be put down.”

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle“She’s pregnant, see it, that bulge?” Wesson says of the brown-colored dog while loading up an aluminum tray of wet food and kibble.

Barbosa and Wesson have been saving animals in Houston for more than a decade, earning K-911 a reputation as a rescue that takes extreme medical cases. These two strays desperately need help, but K-911’s resources are maxed out.

More from Rebecca Hennes: Texas horse rescue finds new home after being evicted due to COVID financial losses

So until space opens up, or a foster agrees to take them, Barbosa and Wesson are feeding and treating strays right on the street, checking in every so often before they can bring them into the program.

Jane Wesson (left) talks with Anna Barbosa of K911 of Houston Animal rescue about how bad the stray dog population has gotten worse since the pandemic on May 15, 2022 in Houston.

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle

Jane Weeson with K911 Houston Animal Rescue prepares dog food to feed stray dogs at the corner of Peach St. and Haywood St. on May 15, 2022 in Houston.

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle

Jane Wesson with K911 Houston Animal Rescue tries to hand feed a stray dog on the corner of Peach and Haywood St. on May 15, 2022 in Houston.

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle

Anna Barbosa with K911 Houston Animal Rescue hand feeds a stray dogs at the corner of Peach St. And Haywood St. on May 15, 2022 in Houston.

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle

Jane Wesson (left) and Anna Barbosa of the Houston animal rescue K-911 feed a pair of stray dogs on May 15, 2022 in Houston. (Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the Chronicle)

“I can’t believe they are still itching after the provecta (flea medication),” Barbosa says.

After feeding, assessing and documenting the dogs’ condition, the women prepare to to leave as the strays head back to the culvert for relief from the blazing sun.

“When you’re out in the field and you have to leave an injured dog out on the street because you literally have no place for it to go, that weighs on you,” Tena Lundquist Faust, co-president of the nonprofit animal welfare organization Houston PetSet said. “You take that with you. You go to bed with that, you wake up with that, and you don’t forget those faces.”

Stray dogs eat after they were fed by K-911 Houston animal rescue volunteers on the corner of Peach St. and Haywood on May 15, 2022 in Houston.

Thomas B. Shea, Contract Photographer / For the ChronicleHouston is in the midst of a stray animal crisis — part of a nationwide drop in adoptions coupled with an uptick in pandemic pet surrenders and abandoned animals — that is leaving volunteer-run rescues, fosters and shelter staff burned out.

“It’s just nonstop, there is no break,” Barbosa said.

Shelters pushed to the max

Houston-area shelters have seen a significant drop in adoptions and fosters that is pushing facilities beyond critical capacity levels.

As the pandemic waned and employees returned to the office, animals started showing back up at shelters in droves. The uptick in evictions after COVID relief programs ended has added to the numbers.

“It seems like everything has slowed down except the intakes,” Rene Vasquez, Fort Bend County Animal Services director, said. The Fort Bend shelter has become so overrun with dogs that staff recently resorted to housing the animals in hallways.

Vasquez said staff are having to bring their jobs home with them on the weekends, taking puppy and kitten litters with them to bottle feed and provide round-the-clock care that fosters would usually provide. The Fort Bend shelter can comfortably care for 170 animals, and as of May 20, it had 200 in its care.

“It just seems like everyone is failing,” Vasquez said.

The average length of stay for animals has also increased. At the Fort Bend shelter, the average length of stay for dogs was about 15 days in 2019. So far in 2022, that average length of stay has increased to 24 days, according to Fort Bend Animal Services Director Barbara Vass. Vass added that there are some outliers, however, and that it is not uncommon to have dogs that stay at the shelter for up to a year.

LONG-STAY PUPS: These Harris County shelter dogs have been waiting for homes for 90+ days

The Montgomery County shelter can now comfortably care for 180 animals, but as of early May the shelter was caring for 275 animals, Aaron Johnson, director for the shelter, said. The facility has seen a significant drop in the number of animals being transferred to rescues: From January 2019 through early May 2019, the shelter transferred 1,042 animals into rescues. During that same time period in 2022, the shelter transferred 534 animals.

The pandemic’s financial toll has played a part in the crisis as well. Many fosters were forced to leave their rescues to find jobs, while shelter staff left for better working conditions in higher-paying industries. Many of the Houston region’s shelters have staff shortages and are struggling to recruit, hire or retain employees. Some, such as BARC, Houston’s municipal shelter, are hiring outside contractors to assist with daily cleanings.

From 2020 to 2022, BARC has seen a nearly 40 percent decrease in animal transfers to rescues, according to city of Houston public information officer Cory Stottlemyer. The shelter is running at a 21 percent deficit in staff, he said.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Stottlemyer cited several recent measures BARC has taken to address the rampant stray pet population, including expanding the shelter’s spay and neuter services to the community, which was bolstered by Houston City Council awarding the shelter $500,000 to offer free spay and neuter services through a partnership with Houston PetSet.

One outlier is the county shelter, Harris County Pets. A shelter representative told the Houston Chronicle in an emailed statement that the pandemic gave shelters a “false sense of reality” after a record number of adoptions were done, but that the challenge of getting pets into homes is no greater than it was before the pandemic. The number of animals transferred into rescues has slowed though: 7,368 were transferred to rescues in 2019; 5,092 in 2020; 4,119 in 2021 and 1,401 through April 2022.

Many municipal shelters had already switched to managed intake during the pandemic, meaning they limited the number of animals they could see and started requiring appointments instead of accepting every animal. Shelters with reduced staff have limited their intake process even further, resulting in more stray animals on the streets that rescues are left to grapple with, including Montgomery and Harris County, BARC and the Houston Humane Society.

NEW TEXAS LAW: What dog owners need to know now that Texas’ new chain tether ban is in effect

“This has also caused a huge influx of animals to be left on the streets and has created a burden for the rescue groups,” said Lundquist Faust.

The crisis — which is unfolding in the midst of a booming kitten and puppy season — has Johnson and Vasquez feeling like all the progress they’ve made in recent years is lost.

“We all feel a little bit discouraged kind of, because we have all been working very hard in this industry to elevate things and this feels like a big hit to the animal welfare community as a whole,” Johnson said.

The issues that maxed-out local shelters are facing trickle down to rescues, which heavily rely on volunteers who foster animals waiting for adoption.

“Fosters used to be a lot more willing to take on a pet, but they have gotten burned out,” Kali Cabrera, founder of Spring Branch Animal Rescue, said.

‘We are sinking’

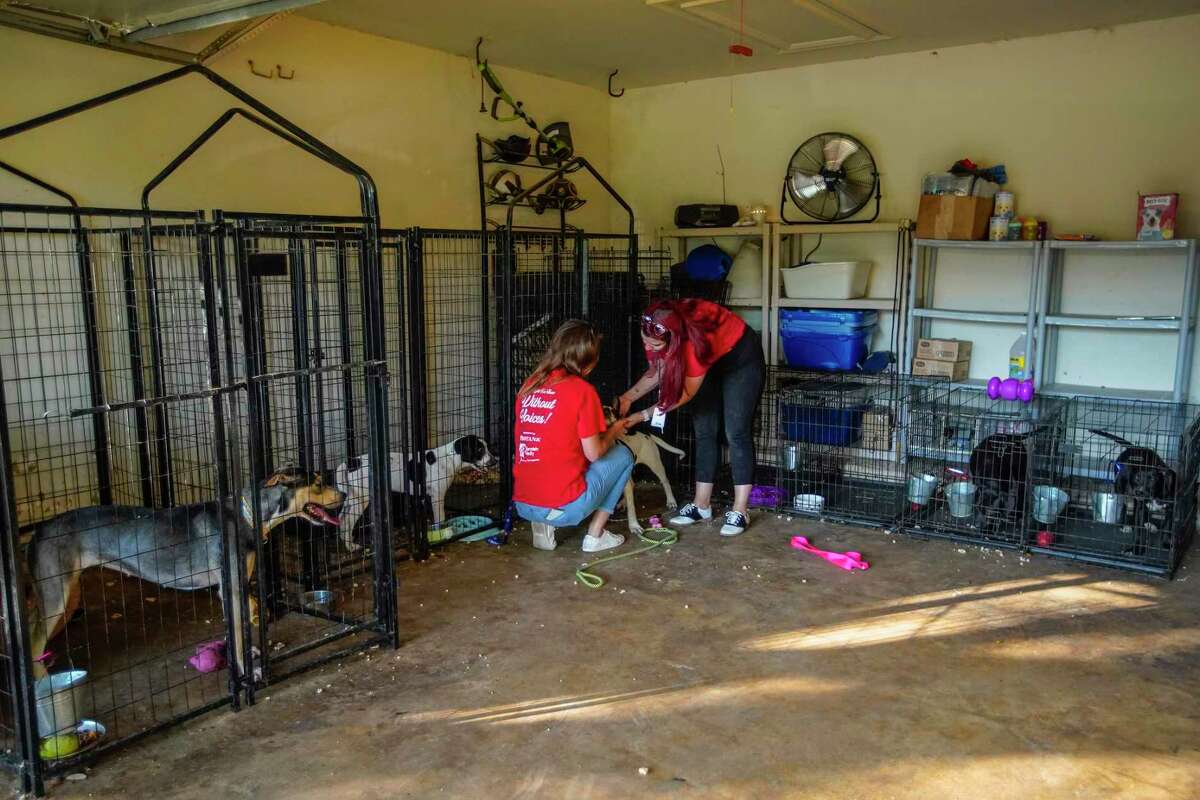

Because of the heavy demand, it’s not uncommon for rescuers to take in the overflow of animals. Some have even turned their homes into makeshift shelters, like Cabrera.

Her Richmond garage is outfitted with kennels and several portable AC and heating units. She currently is caring for seven dogs, but sometimes she has up to double that number.

Kali Cabrera, founder of Spring Branch Rescue, left, with Tatiana Cadena, and Terra Lane, members of her rescue group, as they interact with Mango, a rescue, in her garage at her home, where she houses her rescues on Tuesday, May 17, 2022 in Richmond. Houston-area animal rescues are feeling extraordinary pressures from the nationwide shelter crisis, leading to burnout and compassion fatigue some say is the most extreme they’ve ever endured.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Tatiana Cadena, and Terra Lane, members of Kali Cabrera’s Spring Branch Rescue group, as they worked in her garage at her home, where she houses her rescues on Tuesday, May 17, 2022 in Richmond. Houston-area animal rescues are feeling extraordinary pressures from the nationwide shelter crisis, leading to burnout and compassion fatigue some say is the most extreme they’ve ever endured.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Members of Kali Cabrera’s Spring Branch Rescue group, as they worked in her garage at her home, where she houses her rescues on Tuesday, May 17, 2022 in Richmond. (Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer)

“It feels like we are sinking, and we are trying to stay afloat,” Cabrera said. She added that fosters have also been driven away by long stay times.

“A lot of the organizations have left fosters with animals for six months or longer,” Cabrera said. “We try to work with our fosters so they are in and out, max three months, four months. But we will network the heck out of that pet.”

Kali Cabrera, founder of Spring Branch Rescue, left, with members Terra Lane, center, and Tatiana Cadena, right, with Strawberry and Mango, rescue dogs, in front of her home garage where she houses her rescues on Tuesday, May 17, 2022 in Richmond.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographerTammy Livingston, co-founder of Belle’s Buds Rescue, is also managing an influx of animals at her home in Brookshire. Livingston is currently caring for 16 dogs, and her co-founder, Julia Stanzer-Czaplewski, is caring for 19.

“We constantly are telling ourselves we can’t save them all but as co-leaders we are the ones that take the overflow,” Livingston said. “So then we end up bringing a dog home to us, and now we are overflowing just like the shelters and other rescues.”

Belle’s Buds Rescue co-founders Tammy Livingston, left, and Julia Stanzer-Czaplewski with several of their rescue dogs on their properties on Wednesday, May 18, 2022 in Brookshire.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographerLivingston and Stanzer-Czaplewski are next-door neighbors. They are constructing a building on their shared property to house the overflow of rescue dogs. Once completed, the building will have AC and heating; four indoor and outdoor kennels and a washing area for cleaning puppies, Livingston said.

Belle’s Buds Rescue co-fouders Tammy Livingston and Julia Stanzer-Czaplewski with their rescue dogs in the new the building they are constructing on the property that once finished, will help house the overflow of dogs they take in on their properties on Wednesday, May 18, 2022 in Brookshire. Houston-area animal rescues are feeling extraordinary pressures from the nationwide shelter crisis, leading to burnout and compassion fatigue some say is the most extreme they’ve ever endured.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Belle’s Buds Rescue co-fouders Tammy Livingston and Julia Stanzer-Czaplewski with their rescue dogs in the new the building they are constructing on the property that once finished, will help house the overflow of dogs they take in on their properties on Wednesday, May 18, 2022 in Brookshire. Houston-area animal rescues are feeling extraordinary pressures from the nationwide shelter crisis, leading to burnout and compassion fatigue some say is the most extreme they’ve ever endured.

Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Belle’s Buds Rescue co-founders Tammy Livingston and Julia Stanzer-Czaplewski with their rescue dogs in the new the building they are constructing on the property on Wednesday, May 18, 2022 in Brookshire. (Karen Warren, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer)

“We pay for a lot of this out of pocket,” Cabrera said. “So sometimes I put off paying some bills to take care of some medical stuff.”

The need has become so great that some rescues, especially smaller, more independent ones, are forced to take a break or leave altogether. Others shut down their social media and just operate in limbo, waiting for outside help. Livingston said she has had to close down her rescue’s intake “all the time,” and will update her auto-response on her social media to notify people they are too swamped to help.

There is no easy solution to fixing Houston’s stray animal crisis. Advocates say strict spay and neuter laws are needed, but that’s unlikely to happen any time soon, if at all.

‘HE IS OUR ANGEL’: Remembering Frank, a small Texas town’s celebrity dog

“We need to change the way our city thinks about animals,” Lundquist Faust said. “Our population needs to know about this issue, they need to know how bad it is.”

Lundquist Faust added more city and county resources; improvements at municipal shelters that bring them up to the national standard; and funding from private donors and corporations are needed to alleviate the crisis.

“Although there is compassion fatigue, there is a tiny sense of hope, too,” Lundquist Faust said. “This is one of Houston’s solvable problems. We know that it is, the only thing missing are the resources.”

More Houston and Texas stories